An improvisation translation of ancient Greek poet Sappho's popular Fragment #31 in honour of national poetry day:

It’s as if he were a God, or no better

than one – at least a little lucky, no better

blessed than the best. His bravado really

becomes him there beside you...

But you – your breath’s

softer subtleties laughing, lingering – seeing you

there bewitches me right down

deep to the soul. I have no speech: it all

snapped

away, Lesbia,

while lynching my once-limber limbs stiffly

together in a rising passion-fire,

where in that heat I fountain cold sweat and

beat-beat-faster, grass-green as a lover,

going over and over with my eyes

until I’m blind; unfocussed –

oh

you cannot work in her presence.

Cannot work, never work with her:

she undoes his doings, she completely

undoes him as countless kings have come

undone before.

Thursday 7 October 2010

Sappho Fragment #31 - National Poetry Day

Thursday 30 September 2010

Cold Harbour

Up dark side walls, he discovered

drilling just after noon: he was

drilling, perpendicular

to the supporting slats. He was

perpendicular just after noon.

Evidently very

perpendicular, he loomed,

while three people might have

craned upwards

leaking cold fumes.

Simon Peter Everett, 2010 ©

drilling just after noon: he was

drilling, perpendicular

to the supporting slats. He was

perpendicular just after noon.

Evidently very

perpendicular, he loomed,

while three people might have

craned upwards

leaking cold fumes.

Simon Peter Everett, 2010 ©

Monday 20 September 2010

Not forgetting humility: a short rant about arrogance in writing, in life...

It’s a sad truth that we live in a society saturated by things tailored to inflate our egos. Personal image, consumerism, business top-down cultures and competitive sports – each of these are just examples of the way in which the self is exposed to messages which help us forget something which is possibly one of the most vital parts of being human: humility.

It’s a sad truth that we live in a society saturated by things tailored to inflate our egos. Personal image, consumerism, business top-down cultures and competitive sports – each of these are just examples of the way in which the self is exposed to messages which help us forget something which is possibly one of the most vital parts of being human: humility.Being human condemns us to faults. These faults – although resented and considered a bad thing to possess by many – are actually entirely necessary. If we had no faults, we would not have a perception of what flawlessness might be (however impossible flawlessness is to achieve). What I’m trying to get at in this post is that, yes, there is sometimes a need to be proud and show pride. However, this does not excuse arrogance. Furthermore, as writers sometimes completely lose track of their humility, their work becomes compromised as a result.

We come across the necessity of humility nearly every day: constructive criticism is just an example of how much we come to rely on failure as a means to improve. Accept it. For a writer, this is the most valuable lesson you can learn – to suffer your weaknesses and not ignore them. Despite subjectivity, it is immensely helpful to listen to what others think and to adapt your own work to reflect an acknowledgement of that. That’s not sacrificing an original goal or intention; it is absorbing and intelligently reflecting perspectives hitherto unseen by the author.

What I have noticed throughout my undergraduate course has led me to the conclusion that a writer so stubbornly committed to one idea and way of doing things – his way or no way at all – obsesses too greatly on narrow idea tracks. That is not to say that the individual creative talent is no longer necessary at all; it is the writer from which work emanates. But it’s a lazy way of doing things to ignore advice – or rather, the writer becomes lazy in his own mind without some outside stimulus poking him to attention.

The ego is ever-present and, as such, always will be a huge part of the human condition. It’s equally important to remember that at times it is best for the ego to be slightly less ‘huge’. Respect your own thoughts and beliefs by both trusting and doubting them.

Monday 13 September 2010

Some change, some stasis: The next few days and weeks with shifting dynamics

When we linger for too long in any one place, there is sometimes a sense that you have most definitely outgrown it. However, transitions are also – on occasion – hard to bear as they upset established dynamics. These two forces work at odds with one another: a blend of opposite yet inseparable sensations. It’s important to remember the importance of change, however great or minute. It’s also acutely vital to know when inaction is necessary. Sun Tzu, for example advocates critical timing in ‘The Art of War’ – a brilliant read for confidence and motivation if you’re lacking it. Knowing when not to act, knowing when to act...

Both frustrating, yet – somehow – liberating.

Next week, I’ll be heading back to a familiar place and starting a new course. I will also, in turn, be leaving another familiar place and the end of a relatively disappointing summer. More importantly, this feels very right. It feels as if the critical moment for action has come and it’s the right time to act.

As much as the memories and experiences of the past three years at the University of Kent will be with me, going back there to start afresh once more is also a great opportunity to reassess parts of my life. It’s an uncanny sensation, returning yet moving forward.

Both frustrating, yet – somehow – liberating.

Next week, I’ll be heading back to a familiar place and starting a new course. I will also, in turn, be leaving another familiar place and the end of a relatively disappointing summer. More importantly, this feels very right. It feels as if the critical moment for action has come and it’s the right time to act.

As much as the memories and experiences of the past three years at the University of Kent will be with me, going back there to start afresh once more is also a great opportunity to reassess parts of my life. It’s an uncanny sensation, returning yet moving forward.

Sunday 12 September 2010

I.

They will give you some advice: forget your

flowers and wasted hours. These cage you in

a curtained world where not one eye peeps in,

where you pop pills by the short windowsills

and tremble the netting. There is no breath

that cannot be seen on that pane. Deep night:

when cold moves closer to the fingertip.

When everything suspends. You were thin.

Remember the snow that night? Over those

counted spans I stood smoking as it fell.

Silence; the glint of morning felt distant.

There was sleep: settling snow slept in beds.

If you recall me there – forget that I

knew you were awake, twitching at your hair.

Simon Peter Everett, 2010 ©

flowers and wasted hours. These cage you in

a curtained world where not one eye peeps in,

where you pop pills by the short windowsills

and tremble the netting. There is no breath

that cannot be seen on that pane. Deep night:

when cold moves closer to the fingertip.

When everything suspends. You were thin.

Remember the snow that night? Over those

counted spans I stood smoking as it fell.

Silence; the glint of morning felt distant.

There was sleep: settling snow slept in beds.

If you recall me there – forget that I

knew you were awake, twitching at your hair.

Simon Peter Everett, 2010 ©

Saturday 11 September 2010

A world of difference: why the term ‘earth’ is not the same as ‘world’

There is something that I’ve noticed recently in use of popular terminology which is actually something a lot of people would overlook as insignificant. For the most part, it is. It’s rather inconsequential for most day-to-day life. But if you ever happen to use the terms ‘world’ or ‘earth’ in conversation, then be aware that the two words – although seemingly the same in what they refer to – actually mean entirely different things.

There is something that I’ve noticed recently in use of popular terminology which is actually something a lot of people would overlook as insignificant. For the most part, it is. It’s rather inconsequential for most day-to-day life. But if you ever happen to use the terms ‘world’ or ‘earth’ in conversation, then be aware that the two words – although seemingly the same in what they refer to – actually mean entirely different things.It all hinges on what is physical and what isn’t. That is to say what is actually there in front of us (grass, dirt, mud, trees etc.) versus what is fabricated by us as a race (society, religion and culture). We can touch the ground; we know that it’s there. Can we touch ‘society’? No – not in the same way. We can think of and appreciate the notion of ‘society’, maybe even see it in action as we walk down the street. However, it isn’t a substantial ‘thing’.

This is, on a very basic level, what the difference between ‘earth’ and ‘world’ is. When we say ‘earth’, we’re talking about the bare rock or planet that happens to exist or ‘be’ here. When we talk about ‘world’, we’re actually meaning the ‘earth’ but with human ideologies and practices established within it. So, therefore, we’re living on an ‘earth’ in a ‘world’ which – paradoxically – has in turn given us the opportunity to explore this observation.

It doesn’t stop there though. The notion of ‘world’ can be separated from the ‘earth’ we know of. People are all too keen to create new worlds in science fiction and fantasy; each of these are fabrications of the human mind. The next time you say the term ‘world’, you might have images of Middle Earth bouncing around your head, yes, but it’s nonetheless interesting to know exactly what you’re referring to.

There are a lot of terms in language which are used flippantly without having much thought given to them. This is just one example – there are many others for certain. It does not really serve to show anything in particular, admittedly, yet it might well prove useful to know that there’s a ‘world’ of difference between ‘earth’ and ‘world’ at some point down the line...

Friday 10 September 2010

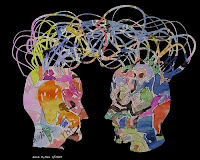

Speaking without saying: A dialogue dilemma! (A not-so-long examination of speech, including minimal amounts of Heidegger)

It’s a familiar situation to find that you have started a conversation with absolute conviction, knowing exactly what you want to say only to find that you’ve ended up garbling some rubbish about nothing in particular. Or it certainly feels like you are. Moreover, the other person probably hasn’t taken a whole lot of notice of anything you’ve said anyway. This is a common feature of any dialogue: feeling a little out of depth, even a touch disconnected from the other person. We can only ever attempt to say things – but are we ever really understood?

A little Martin Heidegger for you now (don’t groan just yet, he has a decent point to make). He says that:

And so...

Not to go into too much analytical depth, Heidegger is basically claiming that we can’t ever actually know what someone is trying to say to us. Let alone this, it’s impossible to really know anything about anyone. I mean really know, as in personal emotions and tastes; not superficially know, for instance how someone might feel starting a new job.

As a result, we are always talking about ourselves. Even to someone else, when we’re trying to say something constructive or helpful: it’s all a disguise. The minute we open a communication with someone, we’re reaffirming our own existence. We say ‘I am here, I am saying this; I am convincing myself of the awareness of my own being’, and ultimately, there’s not a lot we can do about this. It is a quirk of the art of communication which we tend to overlook.

So the next time you feel as if you’ve said nothing much when talking – or absolutely jack all – it’s not something to be ashamed or embarrassed about. You are merely embracing the art of speaking without saying...and you’ve just made Heidegger a very proud man.

A little Martin Heidegger for you now (don’t groan just yet, he has a decent point to make). He says that:

‘communication is never anything like a conveying of experiences, for example, opinions and wishes, from the inside of one subject to the inside of another’

And so...

‘the communication of existential possibilities of attunement, that is, the disclosing of existence, can become the true aim of [...] speech.’

Not to go into too much analytical depth, Heidegger is basically claiming that we can’t ever actually know what someone is trying to say to us. Let alone this, it’s impossible to really know anything about anyone. I mean really know, as in personal emotions and tastes; not superficially know, for instance how someone might feel starting a new job.

As a result, we are always talking about ourselves. Even to someone else, when we’re trying to say something constructive or helpful: it’s all a disguise. The minute we open a communication with someone, we’re reaffirming our own existence. We say ‘I am here, I am saying this; I am convincing myself of the awareness of my own being’, and ultimately, there’s not a lot we can do about this. It is a quirk of the art of communication which we tend to overlook.

So the next time you feel as if you’ve said nothing much when talking – or absolutely jack all – it’s not something to be ashamed or embarrassed about. You are merely embracing the art of speaking without saying...and you’ve just made Heidegger a very proud man.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)